Yes, it was presented that way in BLET in 1994 when I went through. I suspect that was the case until Heien.

Anyone ever taken Mike Lewis' interdiction class? I took it in the early 2000's. This was a point of concern for us as we could clearly see that sub-section "g" stated a (singular) stop lamp. But then you look at "d" which says differently. The local guys in the class conceded that almost everyone would agree that all stop lamps should be working as designed by the manufacturer. Is there anyone, civilian or LEO, that thinks differently? I don't think so. It has been a week since I read Heien but I think the Court mentions this fact. This is why I believe the justices conceded that it was a "mistake of law" and not bad conduct on the officers part. Dude consented to the search...search was not illegal.

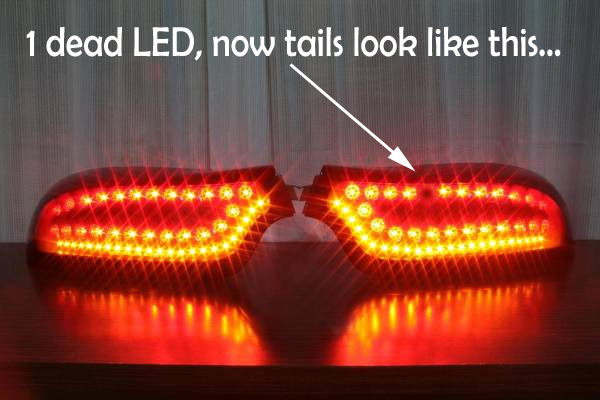

Let's face it. In this instance the law has not kept up with modern safety features. All modern vehicles have at least 2 and from the early 90's they in fact now have 3 stop lamps on the rear of the vehicle. I do not know about other states, but in NC your vehicle will fail inspection if you go there with one (1) stop lamp working.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote